DEPRESSION, MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY IN PATIENTS WITH CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASES

Abstract

Introducere: Depresia a fost identificată de către OMS în anul 2001 drept o boală cronică la nivel mondial, cu probabilitatea să devină principala cauză de morbiditate până în anul 2020 (1). Bolile cardiovasculare reprezintă, în prezent, 48% dintre decesele din Europa, boala coronariană fiind cea mai frecventă cauză (1 din 5 decese) (2). Obiectiv: Această lucrare îşi propune să evalueze riscul de morbiditate şi de mortalitate la pacienţii cu boală cardiovasculară şi depresie comparativ cu pacienţii cu boală cardiovasculară fără depresie. Material şi metodă: Studiul s-a desfăşurat în cadrul secţiei de cardiologie a Spitalului Clinic Colentina, Bucureşti. Studiul este prospectiv, observaţional şi analitic cu o perioadă de urmărire a pacienţilor de 365 de zile. Pacienţii spitalizaţi au fost identificaţi prin consultarea foilor de observaţie și la recomandarea medicilor cardiologi din clinică. Pacienţii au fost evaluaţi din punct de vedere psihiatric conform cu DSM-IV şi ICD-10. Evaluarea cardiologică s-a efectuat de către medicul specialist cardiolog şi a cuprins: examenul obiectiv pe a p a r a t e ş i s i s t e m e , a n a l i z e d e l a b o r a t o r, electrocardiograma, ecografia cardiacă. Rezultate: Riscul de evenimente noi cardiace a fost mai mare la pacienţii cu depresie (HR: 3,5861, Confidence Interval (CI) : 2,1929 to 5,8642), comparativ cu cei fără depresie. Concluzii: Pe perioada studiului, pacienţii cu depresie au prezentat mai multe evenimente cardiovasculare noi. Deşi nu se ştie încă dacă tratarea depresiei poate îmbunătăţi supravieţuirea, se pare că pacienţii cu depresie sunt mai predispuşi la evenimente cardiace noi.

BACKGROUND

A study carried out by the World Health Organization, World Bank and Harvard University concluded that, ever since 1990, depression is the fourth disease cause worldwide (1, 4). Depression has been designated by WHO in 2001 as a worldwide chronic disease, with the potential to become the leading cause of morbidity by 2020 (1).

Cardiovascular diseases represent 48% of all deaths in Europe, with coronary artery disease as the most common cause (1 in 5 deaths) (2).

It is estimated that the prevalence of depression (major depressive disorder) among patients with heart disease is between 15 and 23% (5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10).

In patients with known cardiac disease, depressive disorder is responsible for an increase of approximately 3-4 fold increased risk of cardiovascular mortality (6, 11, 12, 13, 14).

Diagnosis and treatment of major depression is important because many international studies have shown that depressive symptoms are a predictor for development of cardiovascular disease and unfavorable prognosis. Depression is associated with multiple physiological changes that can adversely contribute to the development of cardiovascular disease and unfavorable prognosis. Depression is associated with multiple physiological changes that can adversely contribute to the development and prognosis of heart disease. Patients with depressive symptoms present in response to emotional stress, the activation of the sympathetic nervous system and the h y p o th alamic- p itu itar y – ad r en al co r tical s y s tem. Following the activation of the two systems appear: hipercortizolemia, high levels of catecholamines in the blood, abnormal platelet activation, increased inflammatory markers and endothelial dysfunction. These physiological changes are also present in depressed patients without heart disease. After the disappearance of the two systems stressors they should return to their basal levels (15, 16, 17). Genetic predisposition, such as the serotonin transporter gene polymorphism and the presence of environmental factors could explain why some people adapt to stress factors, while others develop depression (18). Excessive activation of hypothalamic- pituitary-adrenal axis is manifested by elevated levels of cortisol and catecholamines (adrenaline and noradrenalin) and resistance to dexamethasone suppression test. The high level of catecholamines lead to vasoconstriction and increased heart rate, which may be beneficial in the short term response to stress, but on long term can lead to heart failure. Increased levels of catecholamines are related to cardiac mortality by left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure (19, 20, 21, 22).

OBJECTIVES

The study aims to determine the role of depression as a prognostic factor for cardiovascular disease. In this sense, the objective of this paper is to analyse the risk of morbidity and mortality in patients with cardiovascular disease and depression in comparison with those with cardiovascular disease but without depression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

I. General:

The study was conducted in the Cardiology Department of Colentina Clinical Hospital, Bucharest. Hospitalized patients were identified for psychiatrical evaluation by consulting the observation sheets and by the reference from the cardiologists. Those who were assessed were informed about the following study and signed a consent form. Patients were psychiatrically evaluated and diagnosed conform with DSM-IV and ICD-

10. In addition patients completed the self-assessment Beck Depression questionnaire (Beck Depression Inventory, BDI). For patients who meet the diagnosis of depressive disorder according to DSM-IV criteria (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition) and ICD-10 criteria (The ICD-10

Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders), to a s s e s s t h e s e v e r i t y o f d e p r e s s i o n , I u s e d : M o n t g o m e r y – A s b e rg D e p r e s s i o n R a t i n g S c a l e (MADRS), Hamilton Depression Scale with 17 items (HAM-D) and Hamilton Anxiety Scale with 14 items (HAM-A). Cardiological assessment was done by the cardiologist and included: physical examination, laboratory tests (blood count, biochemistry, electrolytes, inflammatory markers – fibrinogen, erythrocyte sedimentation rate – ESR, C-Reactive Protein, markers of markers of heart failure – NTpro-BNP), electrocardiogram (ECG), echocardiography (especially evolution of the left ventricle ejection fraction, EF%).

The patients were selected by considering inclusion and exclusion criteria.

II. Inclusion criteria:

– Subjects (adults of both sexes) aged over 18

– Patients with acute coronary syndrome (acute MI or unstable angina who were hospitalized), stable angina, heart failure or arrhythmias.

III. Exclusion criteria:

1.Cardiovascular. Exclusion criteria were: (a) heart surgery scheduled anytime in the next 6 months (b) current episode of unstable angina or MI in more than three months after surgery for aorto – coronary bypass (CABG).

2.Medical otherwise. Other exclusion criteria were medical: (a) viral, bacterial, parasitic infections that can independently increase inflammatory markers, (b) type I or II diabetes uncontrolled or newly diagnosed (c) significant renal or hepatic dysfunction or other serious extracardiac diseases, (d) pregnant or within 4 weeks post partum.

3.Psychiatry. Were excluded from study patients with:

(a) abuse or dependence on alcohol or drugs in last 6 months,

(b) psychotic symptoms, history of psychotic disorder,

(c) psihoorganic syndrome, dementia (Mini-Mental State Examination score, MMSE < 23),

(d) a significant suicide risk.

IV. Study design:

The study is prospective, observational and analytical.

Patients who met inclusion criteria were followed for a period of one year after enrollment and had four study visits: at baseline, 3 months, 6 months and 1 year. Hospitalized patients were identified for psychiatrical evaluation by consulting the observation sheets and by the reference from the cardiologists. There were also recorded (from patient and relatives), personal data (marital status, education level and profession), informations about the history of the patients: family history, history of cardiovascular disease and where there was possible, information about the onset and history of depressive symptoms (in most of the cases, the diagnosis of depressive disorder was established at the inclusion in the study).

At baseline and at each study visit patients had psychiatric examination (conform with DSM-IV, ICD-10) and assessment of depression was made with scales: BDI, MADRS, HAM-D, HAM-A) and clinical and paraclinical c a r d i o l o g i c a l e x a m i n a t i o n ( l a b o r a t o r y, E C G , echocardiography). Control group (cardio-vascular patients without depression) had the same examinations. The group of patients with cardiovascular disease and depression was compared with the group of patients with cardiovascular disease without depression, in terms of tracking parameters and their evolution.

Study design allowed application of scales in a single study visit. Design and methodology of the study was conceived so to be achieved relative easy in terms of logistics of the study, trying to maintain an adequate scientific level.

V. Statistical analyses:

Survival curves were generated by the Kaplan-Meier

RESULTS

According to the design of the study, there were followed a total number of 186 patients (100%) with a definite cardiovascular diagnosis.

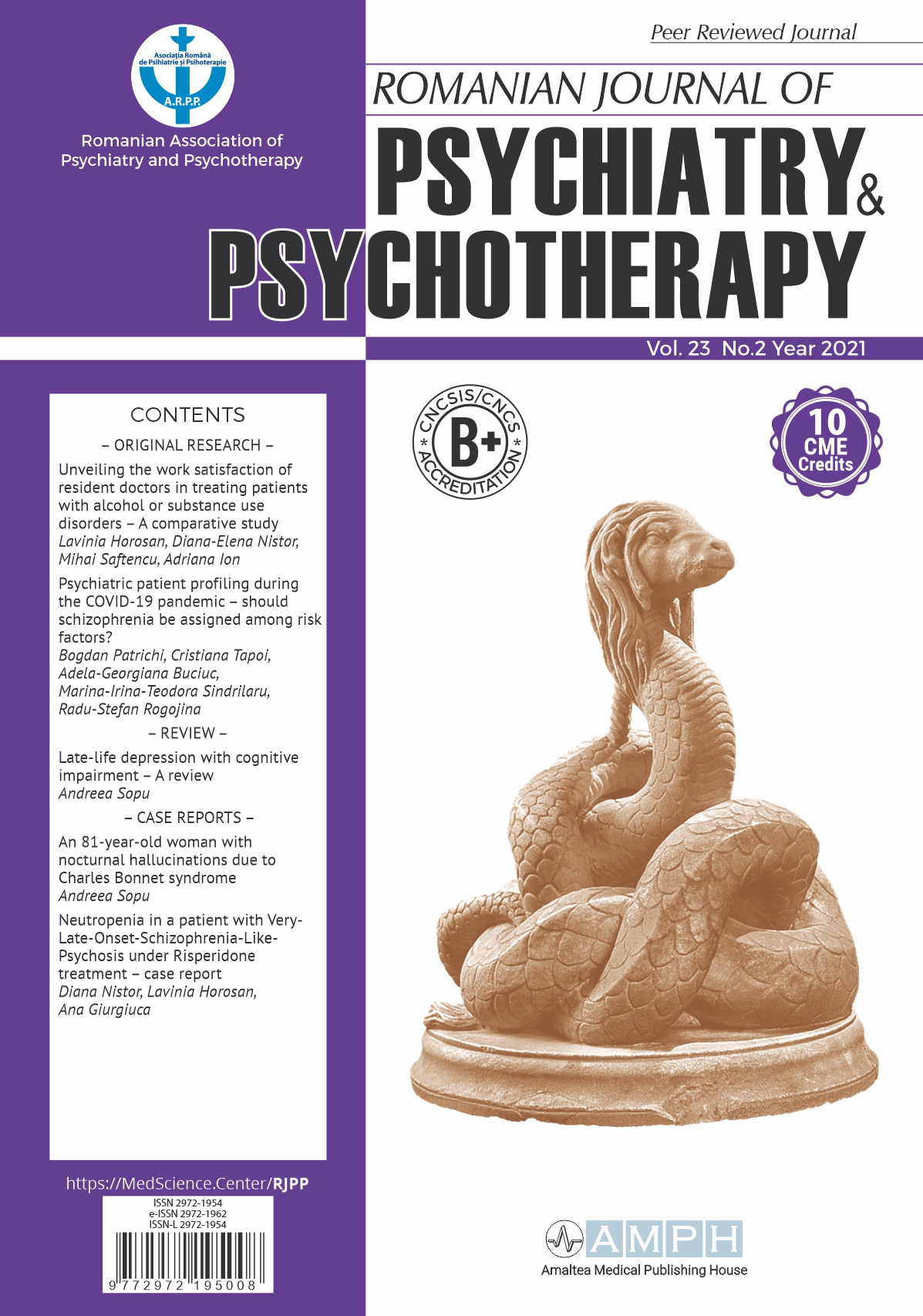

This patients were initially divided in two groups: 97 patients (52,15%) diagnosed with ischemic heart disease and 89 patients (47,85%) with non-ischemic heart disease (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The repartition of the patients taken into the study depending of the type of cardio-vascular disease.

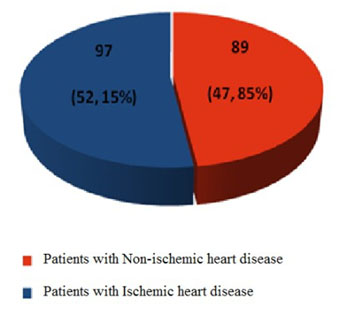

Further it was performed the screening of all patients for depression. Out of the 186 patients , 110 (54,19%) suffered from depression (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Distribution of the patients according to the the results of the screeening for depression

There were 24 (12,9%) deaths during the follow-up (365 days). The deaths occurred at the patients with cardiovascular disease and depression.

We must mention that there were no deaths in the group of patients with cardiovascular disease without depression. Most of the deaths were observed at 3 months during the follow-up: 9 deaths (37,50%). There were observed 7 deaths (29,17%) at 6 month and 8 deaths (33,33%) at 12 months.

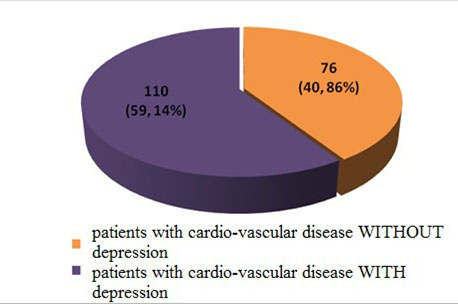

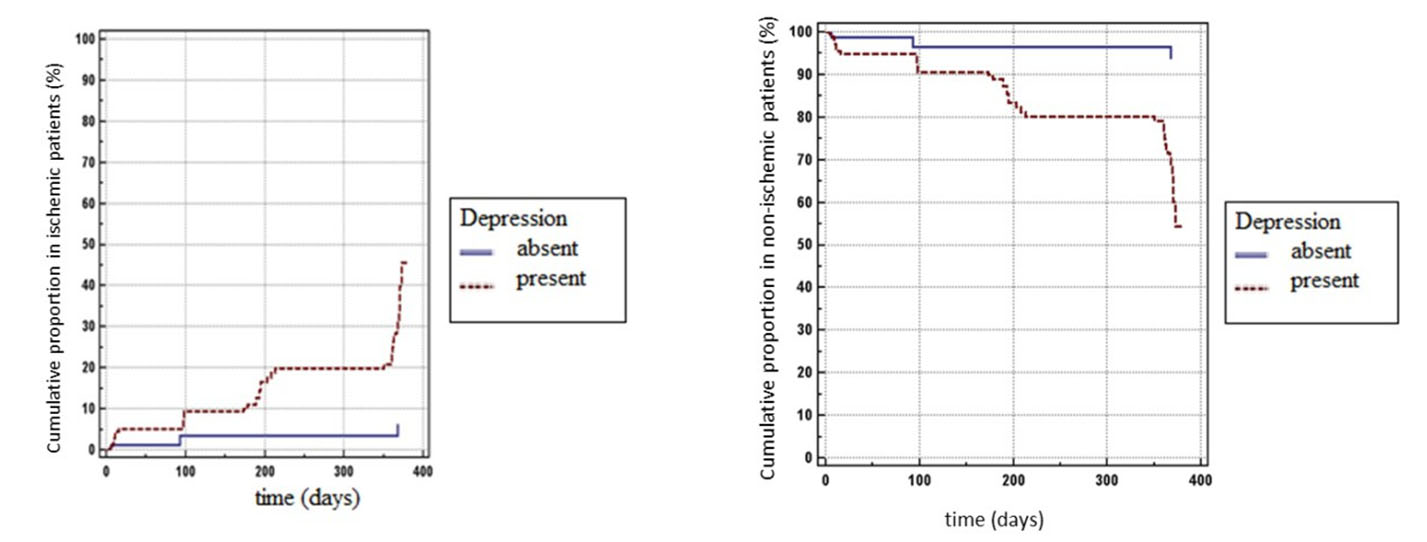

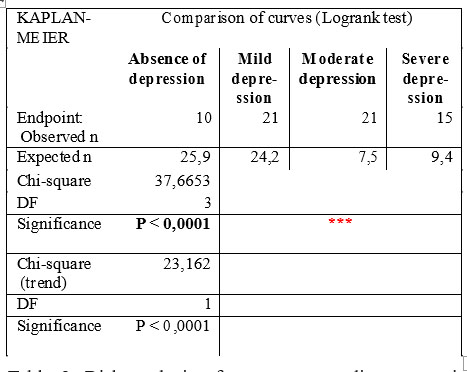

Further, we calculated the probability of occurrence of new cardiac events, for the patients with cardiovascular disease and depression, and for the patients without depression, using the Kaplan-Meier survival curves. For this calculations we excluded the deaths because of the possible fals statistical results that could occure. We observed that there were 10 new cardiac events in the group of the patients without depression, while in the group of patients with depression there were 57 new cardiac events.

The risk of new onset cardiac events were 3,5861 fold higher (HR: 3,5861, Confidence Interval (CI) :

2,1929 to 5,8642) for the patients with depression, comparing with those without depression.

At the end of the study, the proportion of the patients without depression and new cardiac events reaches 6,4%, and the proportion of the patients with depression and new cardiac events reaches 45,5%, leadind to a statistic significant difference (p < 0,0001) (Figure 3. and Table 1).

Table 1. Risk analysis of new onset cardiac events in ischemic patients and in non-ischemic patients based on the presence / absence of depression over total follow-up period

Figure 3. Cumulativ proportion of new cardiac events in ischemic patients and in non-ischemic patients based on the presence of depression over total follow-up period, using Kaplan–Meier curves

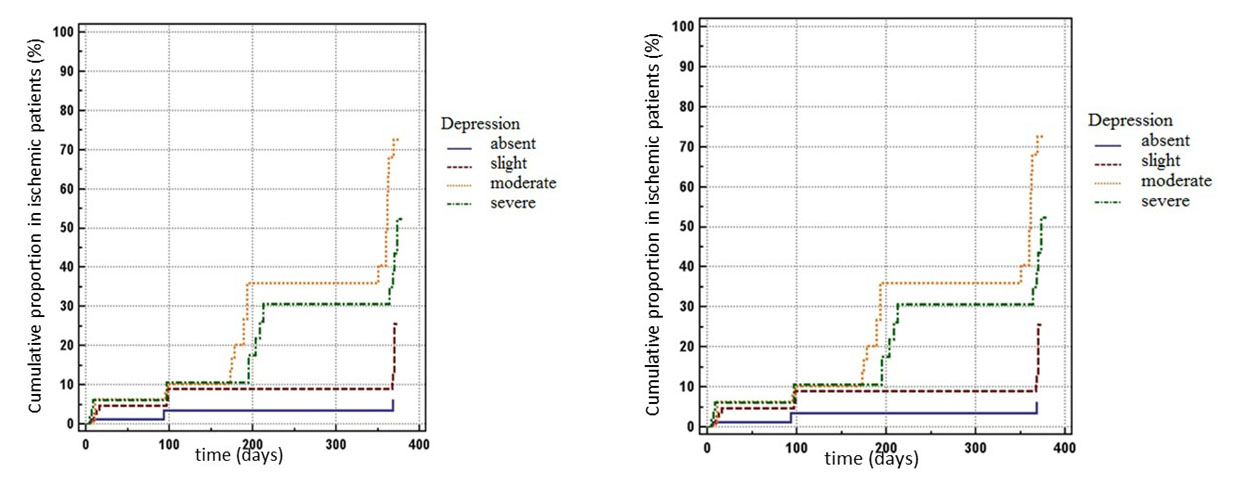

Figure 4. Cumulativ proportion in ischemic patients and in non-ischemic patients based on depression severity over total follow-up period, using Kaplan–Meier curves

Note: In the left chart: bottom curve, no depression; second curve, mild depression, third curve, severe depression, top curve, moderate depression. In

the right chart: top curve, no depression; seccond curve, mild depression; third curve, severe depression; bottom curve, moderate depression.

Based on the depression scores, the patients were diagnosed with : no depression, mild depression, moderate depression and severe depression. There were no deaths at patients without depression. Most of the deaths were observed at patients with moderate depression 13 (54, 17%); at patients with mild depression were found 4 deaths (16, 67%) and 7 (29, 17%) deaths were found at patients with severe depression.

As we already mentioned, there were 57 new cardiac events in the group of patients with depression. At the end of the follow-up period, based on the depression scores, the cumulative proportion of the patients with new cardiac events were : 6,4% at the patients without depression, 25,6% patients with mild depression, 72,6% at the patients with moderate depression and 52,6% at the patients with severe depression. The diferences between the groups with different severity of depression were statistical significant (p < 0, 0001). As we can see the most new cardiac events appear at the patients with moderate severity of depression (Figure 4. and Table 2.).

Table 2. Risk analysis of new onset cardiac events in ischemic patients and in non-ischemic patients based on the severity of depression over total follow-up period

DISCUSSIONS

In our study the risk of new cardiac events were 3,5861 fold higher for the patients with depression (HR:

3,5861, Confidence Interval (CI) : 2,1929 to 5,8642), comparing with those without depression.

The results of our study are concordant with the results of the international studies.

Multiple studies conclude that in patients with known cardiac disease, depressive disorder is responsible for an increase of approximately 3-4 fold the risk of cardiovascular mortality (6, 11, 12, 13, 14).

In a meta-analysis of 20 studies from 2004, Barth J et al. concluded that depressive symptoms increases mortality risk 2.24 times at two years in patients with coronary heart disease, even after adjustment for other risk factors, but without significant effect in the first 6 months of follow up (23). Study of Fresure-Smith et al. showed that depression diagnosed during hospitalization for myocardial infarction is a negative prognostic factor, both at 6 months and 18 months, independent of other consecrated prognostic factors (24).

Also, in patients with heart failure, depression is associated with health status decline and increased rates of rehospitalization and mortality (25).

A separate analysis by Frasure-Smith and colleagues, showed that depression predicts long-term cardiovascular mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure with ejection fraction less than or equal to 35%. Depression significantly increased cardiovascular mortality (hazard ratio [HR], 1.57), arrhythmic death (HR, 1.69), and total mortality (HR, 1.38) within a follow-up of 39 months despite an optimized treatment and control for other prognostic indicators (26).

Regarding the severity of depression and the risk of new cardiac events, in our study, most of the new cardiac events appear at the patients with moderate severity of depression.

According to Bush DE et al., even minimal symptoms of depression increase mortality risk after acute myocardial infarction (13).

From all the 24 deaths that were observed in our study, most of them (9 patients – 37, 50 %) appeared at 90 days of follow-up. In a substudy of the OPTIMIZE-HF Hospitalized Patients With Heart Failure) trial, patients with depression were more likely to have a longer hospital stay and higher 60- to 90-day postdischarge mortality (27).

Depression also has been shown to be a risk factor for recurrence of atrial fibrillation. Symptoms of depression significantly predicted recurrence of abnormal cardiac rhythm by 2 months of follow-up in patients with atrial fibrillation / atrial flutter who had been successfully cardioverted. This result was postulated to be due to a heightened adrenergic tone and a proinflammatory state (28).

CONCLUSIONS

During the follow-up, the patients with depression had more new cardiac events. Although it is not yet known whether treating depression can improve survival, it seems that the patients with depression are more likely to be predisposed to new cardiac events.

Our study support the need to establish early detection (screening) and treatment of depression in patients with cardiovascular disease for the following reasons:

– poor diagnosed depression in patients with medical conditions and therefore those with cardiovascular disease

– as a co-morbidity, depression contributes to the worsening of the symptoms , prognosis and the growth of mortality from cardiovascular disease

– if depression influences the physiological mechanisms of cardiovascular disease, early diagnosis and treatment of depression may lead to an evolution and a better prognosis by returning to the basal function of these mechanisms

– if depression affects cardiovascular disease through behavioral changes, early diagnosis and treatment of depression can improve adherence to therapy, changing lifestyles and cardiology dispensary.

REFERENCES

1. Lopez AD, Murry C. The Global Burden Of Disease, 1990-2020. Nature Medicine 1998; 4(11):1241-1243.

2. British Heart Foundation. European Cardiovascular Disease Statistics. London: British Heart Foundation, 2008.

3. Khandelwal S. Conquering Depression: You Can Get Out Of The Blues. WHO, 2001, 6-27.

4. Ustün TB, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Chatterji S, Mathers C, Murray CJ. Global Burden Of Depressive Disorders In The Year 2000. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:386-92

5. Ariyo AA, Haan M, Tangen CM et al. Depressive Symptoms and Risks of Coronary Heart Disease and Mortality in Elderly Americans. Circulation 2000;102:1773-1779.

6. Lesperance F, Frasure-Smith N, Juneau M, Theroux P. Depression and 1-year Prognosis In Unstable Angina. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:1354- 1360.

7. Carney RM, Freedland KE, Sheline YI, Weiss ES. Depression and Coronary Heart Disease: a Review for Cardiologists. Clin Cardiol 1997;20:196-200.

8. Schleifer SJ, Macari-Hinson MM, Coyle DA et al. The Nature and Course of Depression following myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med 1989;149:1785-1789.

9. Jiang W, Alexander J, Christopher E et al. Relationship of Depression to Increased Risk of Mortality and Rehospitalization in Patients with Congestive Heart Failure. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:1849-1856.

10. Koenig HG. Depression in Hospitalized Older Patients with Congestive Heart Failure. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1998;20:29-43.

11. Schulman J, Shapiro PA. Depression and Cardiovascular Disease. What is the Correlation? Psychiatric Times 2008;25(9):1-8.

12. Glassman AH, O’ Connor CM, Califf RM et al. Sertraline Treatment of Major Depression in Patients With Acute MI or Unstable Angina (SADHART). JAMA 2002;288:701-709.

13. Bush DE, Ziegelstein RC, Tayback M et al. Even Minimal Symptoms of Depression Increase Mortality Risk After Acute Myocardial Infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:337-341.

14. Welin C, Lappas G, Wilhelmsen L. Independent Importance of Psychosocial Factors for Prognosis After Myocardial Infarction. J Intern Med 2000;247:629-639.

15. Rozanski A, Blumenthal JA, Kaplan J. Impact of Psychological Factors on the Pathogenesis of Cardiovascular Disease and Implications for Therapy. Circulation 1999;99:2192-2217.

16. Lett HS, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Sherwood A, Strauman T, Robins C, Newman MF. Depression as a Risk Factor for Coronary Artery Disease: Evidence, Mechanisms, and Treatment. Psychosom Med 2004; 66: 305–315.

17. Lederbogen F, Gilles M, Maras A, Hamann B, Colla M, Heuser I, Deuschle M. Increased Platelet Aggregability in Major Depression? Psychiatry Res 2001;102:255–261.

18. Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE et al. Influence of Life Stress on Depression: Moderation by a Polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science. 2003;301:386–389.

19. Heit S, Owens MJ, Plotsky PM, Nemeroff CB. Corticotropin- Releasing Factor, Stress, and Depression. Neuroscientist 1997;3:186- 194.

20. Otte C, Marmar CR, Pipkin SS et al. Depression and 24-hour Urinary Cortisol in Medical Outpatients with Coronary Heart Disease: Biol Psychiatry 2004;56:241-247.

21. Pepper GS, Lee RW. Sympathetic Activation In Heart Failure And Its Treatment With Beta-Blockade. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:225-234.

22. Benedict CR, Shelton B, Johnstone DE et al. Prognostic Significance of Plasma Norepinephrine in Patients with Asymptomatic Left Ventricular Dysfunction. Circulation 1996;94:690-697.

23. Barth J, Schumacher M, Herrmann-Lingen C. Depression as a risk factor for mortality in patients with coronary heart disease: a meta- analysis. Psychosom Med 2004;66: 802–813.

24. Fraser-Smith N, Lesperance F, Talajic M. Depression and 18-month prognosis after myocardial infarction. Circulation 1995;91: 999–1005.

25. York KM, Hassan M, Sheps DS. Psychobiology of depression/

distress in congestive heart failure. Heart Fail Rev 2009 ;14: 35–50.

26. Frasure-Smith N, Lespérance F, HabraM, et al.: Elevated depression symptoms predict long-term cardiovascular mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure. Circulation 2009, 120:134–140.

27. Albert NM, Fonarow GC, Abraham WT et al. Depression and clinical outcomes in heart failure: an OPTIMIZE-HF analysis. Am J Med 2009;122: 366–373.

28. Lange HW, Herrmann-Lingen C. Depressive symptoms predict recurrence of atrial fibrillation after cardioversion. J Psychosom Res 2007;63: 509–513.

***