DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF A ROMANIAN ADAPTATION OF THE 20-ITEM TORONTO ALEXITHYMIA SCALE (TAS-20-RO)

Abstract

Introducere: Scopul acestui studiu a fost de a dezvolta și valida traducerea in limba romană a Scalei pentru Alexitimie Toronto, cu 20-itemi (TAS-20), folosind un eșantion cu elevi români. Metodă: Versiunea originală în limba engleză a TAS-20 a fost tradusă în limba română, după care a fost din nou- tradusă în limba engleză până când limba echivalenta a fost stabilită. Versiunea în limba română a TAS-20 (TAS- 20-Ro), a fost apoi administrată la 225 de studenți de la Universitatea Babeș-Bolyai din Cluj-Napoca, România. Analizele factorului de confirmare au fost efectuate, și cinci modele diferite au fost comparate. Au fost evaluate fiabilitatea internă și validitatea factorială. Rezultate: TAS-20-Ro a demonstrat fiabilitate internă și corelatii structurale adecvate a trei factori tradiționali ai scalei. Concluzii: TAS-20-Ro este o măsură valabilă și fiabilă a alexithymiei in lotul de studenți din studiu și poate fi un instrument potrivit pentru investigarea alexitimiei în alte probe de populație vorbitoare de limba română. Cu toate acestea, fiabilitatea și validitatea factorială a scalei trebuie să fie stabilite într-un eșantion clinic, și sunt necesare studii suplimentare pentru a evalua validitatea convergentă și discriminantă a TAS-20-Ro

INTRODUCTION

Alexithymia is multifaceted personality construct that has been associated with a variety of medical and psychiatric disorders, in particular eating disorders, substance use disorders, functional gastrointestinal disorders, post-traumatic stress disorders, and functional somatic syndromes (1-3). Formulated by Nemiah, Freyberger, and Sifneos (4) during the 1970s, the construct encompasses the following salient features: (a) difficulty identifying subjective feelings and distinguishing them from the somatic sensations that accompany emotional arousal; (b) difficulty describing feelings to other people; (c) an externally-oriented cognitive style; and (d) constricted imaginal processes, as evidenced by a paucity of fantasies. During the past two decades empirical research on alexithymia has provided evidence supporting the validity and dimensional nature of the construct, identified some neural correlates of the construct, explored the influence of genetic and environmental/developmental factors in its etiology, and demonstrated that alexithymia can have a negative impact on treatment outcomes (1, 5-7). The most frequently and widely-used measure of alexithymia is the self-report 20- item Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) (3, 8, 9). The items of the TAS-20 are organized into three factor scales that map onto the theoretical conceptualization of alexithymia – Difficulty Identifying Feelings (DIF), Difficulty Describing Feelings (DDF), and Externally Oriented Thinking (EOT); in addition to assessing an externally-oriented cognitive style, the EOT factor scale indirectly assesses the constricted imaginal processes facet of the construct (9, 10). The TAS-20 has been translated into more than 20 languages and its three- factor structure cross-validated by confirmatory factor analysis in Western, Eastern European, East Asian, and Middle Eastern countries (11-14). By demonstrating that the structure of the construct is equivalent across many cultures, these findings support the view that alexithymia is a universal trait rather than a culture-bound construct.

Although it appears that Romanian translations of the TAS-20 have been developed, to our knowledge none of them have been evaluated empirically. For example, Haita, Nistor and Szabo (15) used the TAS-20 to investigate stress affects and burnout rate in Romanian people in physically and mentally demanding jobs like the military, police force, and piloting. Similarly, Lala, Bobirnac, Tipa, and Davila (16) used the TAS-20 to assess alexithymia in a Romanian-speaking student sample. However, the authors of these studies did not specify which translation of the TAS-20 was used and whether it had been cross-validated. Given the failure to report the psychometric properties of the scale, the validity of the findings may be questionable. It is essential that the reliability and factorial validity of translated versions of scales be demonstrated before they are used for research or clinical purposes.

The purpose of the current study was to develop a Romanian translation of the TAS-20 and to evaluate its reliability and factorial validity in a student sample. For practical purposes we chose to collect data for the study by administering the Romanian adaptation of the TAS-20 via the Internet, a method being used increasingly by researchers as it reduces the financial cost of studies, enables collection of data very quickly from large numbers of participants, and lowers the chance of human error as the data is entered automatically into a database (17). Previous research has demonstrated that Internet and pencil-and-paper methods of administering the TAS-20 are comparably reliable, and that the factor structures and external validity are equivalent (18).

METHOD

Participants and Procedure

The participants in the study were 225 university students (25 men; 195 women, missing gender data for five participants) ranging in age from 18 to 47 years with a mean age of 23.7 years (SD = 5.19). The sample consisted of psychology students from the Babes-Bolyai University (BBU) in Cluj-Napoca, Romania, who were invited to complete a web-based format of the TAS-20-Ro via an email sent to the psychology listserv of the University. The psychology listserv of BBU consisted of approximately

1000 students, which included current undergraduate and graduate students, as well as, occasionally, former students of BBU who had not removed their email addresses from the listserv upon graduation or termination of studies. Any student taking courses in the psychology program at BBU may enlist in the psychology university listserv at any point during their study period; however, it is common to enlist during the first year of study. The majority of the sample (98.7%) indicated that they were born in Romania and that their first language was Romanian. The majority of the students were single (n =

202), 17 indicated they were married, 4 were divorced,and 2 indicated “other”. All of the participants volunteered for the study and provided online consent; participants were not offered compensation of any kind for their participation.

Instrument

Twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale. The TAS-20 is a 20 item self-report instrument, with each item rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree); five of the items are negatively keyed. As noted earlier, the TAS-20 consists of three factor scales: DIF (7 items), DDF (5 items), and EOT (8 items) (8, 9, 19). Total scores on the scale range from 20 to 100.

The English version of the TAS-20 was translated into the Romanian language using the back- translation method described by Del Greco, Walop and Eastridge (20). The TAS-20 was initially translated into Romanian by the first author and then translated back into English by a close friend of the first author who spoke Romanian as a first language, and who was independent of the study and blind to the original English version of the scale. Authors of the original English version (R.M Bagby and G.J. Taylor) reviewed the back-translated version and made suggestions for several revisions to the translation. After two rounds of translation and back-translation, consensus was reached that cross-language equivalence was achieved.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive and reliability analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS 20.0) (21). Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were conducted using Mplus version 7.0 software (22). In this study, items were treated as ordered categorical variables in order to avoid misleading results from treating items as continuous (23). Therefore, all confirmatory factor analyses were conducted using the Weighted Least Squares Means and Variances adjusted (WLSMV) estimator and analyzing the matrix of polychoric correlations, which is robust to modest violations of underlying normality (23).

Consistent with previous evaluations of Chinese, Dutch, German, Greek, and Russian translations of the TAS-20, we evaluated and compared the factor solutions for several different models of the scale. The following five models were evaluated:

(a)Model 1 is a 1-factor model.

(b)Model 2 is a 2-factor model where factor 1 comprises the DIF and DDF items and factor 2 comprises the EOT items.

(c)Model 3a is the standard 3-factor model (DIF, DDF, and EOT) reported by the developers of the TAS-20 (8). (d)Model 3b is an alternative 3-factor model in which factor 1 comprises the DIF and DDF items, factor 2 consists of the “pragmatic reasoning” (PR) items from EOT (items 5, 8, and 20), and factor 3 consists of the “importance of emotions” (IM) items from EOT (items

10, 15, 16, 18, and 19), as suggested by Müller, Bühner, and Ellgring (24).

(e)Model 4 is a 4-factor model with DIF and DDF as separate factors, and EOT divided into a PR factor (3 items) and an IM factor (5 items).

To evaluate model fit we used the following goodness of fit indices: Weighted Root Mean square Residual (WRMR), the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) along with its 90% confidence interval. The following standards were used to

assess the model fit: WRMR ≤ 1 (25); TLI and CFI ≥ 0.90 (26); and RMSEA < 0.08 (27). To evaluate internal reliability and item-to-item homogeneity we calculated coefficient and mean inter- item correlations (MICs) for the total TAS-20-Ro and for each factor scale. The criterion standards set were > .70 for coefficient and .15 to .50 for the MICs (28, 29). Assessment of broad domains, such as the TAS-20 total score, would be expected to have MICs in the lower end of this range, and assessment of more narrow-level constructs, such as the factor scores, would be expected to have MICs in the higher end of this range.

RESULTS

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

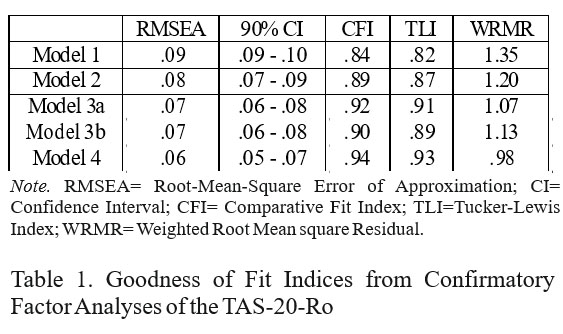

The goodness of fit indices for each of the five models tested are shown in Table 1.

Examination of these indices reveals that Models

1 and 2 did not achieve adequate fit. The three remaining models appear comparable. However, Model 3b has slightly lower CFI and TLI and higher WRMR than the o t h e r r e m a i n i n g m o d e l s . M o d e l 4 , a l t h o u g h demonstrating adequate fit, does not lend itself to meaningful interpretation as the 3-item PR factor demonstrated large statistically significant correlations with the DIF (r = .89), DDF (r = .81), and IM (r = .88) factors, suggesting that a three factor model is likely more meaningful. Further, although all three items had statistically significant loadings on the PR factor, item 5 (negatively keyed) demonstrated a weak loading (.23) indicating much of the variance associated with this item is not well captured by this factor, leaving the other two items as the sole indicators. Typically at least three

substantial indicators (loadings of ≥ .30) are required to

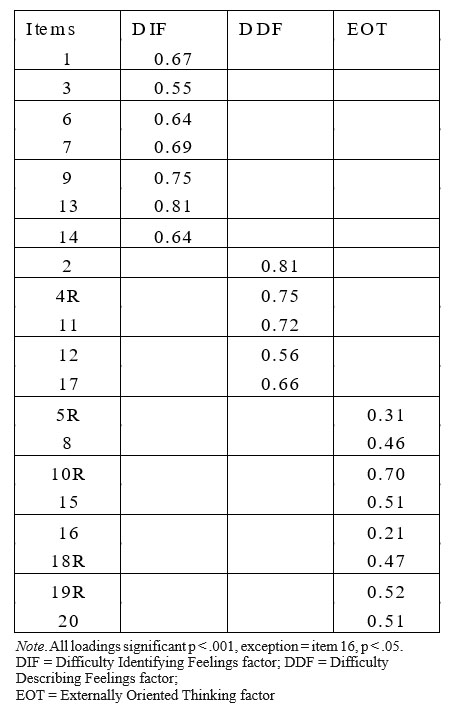

specify a factor. Thus, model 3a, the standard three factor model, provided the best and most interpretable fit to the data. Item factor loadings from the CFA for Model 3a are shown in Table 2.

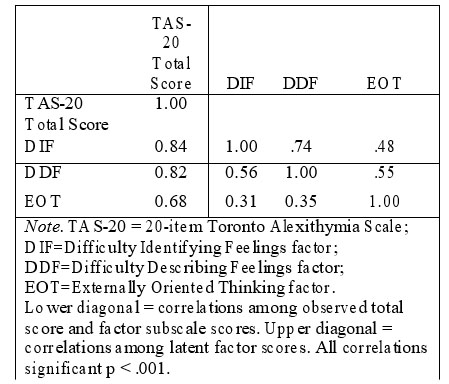

Correlations among the three latent factors and observed correlations among the TAS-20-Ro total score and the three factor scale scores for this standard three factor model are reported in Table 3.

Means and Standard Deviations (SDs), and Reliability for the TAS-20-Ro and its Factor Scales

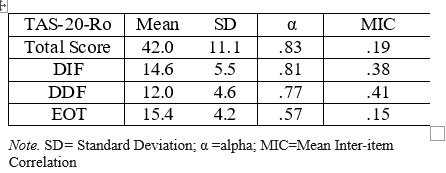

The means, SDs, internal consistency reliability coefficients, and MICs for the TAS-20-Ro and its three factor scales are presented in Table 4.

The coefficients for the TAS-20-Ro total scale and the DIF and DDF factor scales are well above the standard of .70, indicating adequate internal consistency. The alpha coefficient for the EOT factor scale is .57, which is below the acceptable level. The MICs for the total TAS-20-Ro and the DIF, DDF, and EOT factor scales are all within the range of .15-.50, which is the range recommended for multifactor scales assessing broad constructs (29, 30).

Table 2. Factor loadings from standard 3-factor model of the TAS-20-Ro

Table 3. Correlations among TAS-20-Ro total score and factor scores (N = 225)

Table 4. Means, SDs, Cronbach alpha, and Mean Inter- item Correlation Coefficients

DISCUSSION

The overall aims of this study were achieved. The TAS-20 was translated into Romanian and cross- language equivalence was established. Internal reliability and adequate fit of the standard three factor structure of the TAS-20-Ro were demonstrated in a university student sample. The results of the internal reliability of the total scale are comparable to those obtained with the original English version (8), as well as other versions, including Chinese, Greek, Russian, and Swedish translations of the scale (12-14, 31). Similar to results reported for the original English derivation sample of university students (8), the internal reliability estimates for the DIF and DDF factor scales are above the standard of .70, and the mean inter-item correlation coefficients are within the recommended range of .15-.50, indicating adequate homogeneity of item content. Although the internal reliability estimate for the EOT factor scale is well below the standard, and the mean inter-item correlation coefficient of .15 is slightly low for the assessment of narrow band constructs, EOT assesses a broader universe of content than either DIF or DDF, suggesting that the MIC for EOT was also within the acceptable range recommended by Simms and Watson (29). Less than optimal internal reliability coefficients estimates have been reported for the English version of the TAS-20 (14) and for many translations of the scale (11-14), which has led to the suggestion that the items assessing externally- oriented thinking may need some revision. Nonetheless, significant correlations were demonstrated between observed scores on EOT and the total score as well as among latent factors.

Comparing the fit of five different factor solutions, it was determined that the 1-factor and 2-factor models, and also a 3-factor model in which the DIF and DDF items form one factor and the EOT items are separated into a PR factor and a IM factor, demonstrated poor fit for the TAS-2-Ro. These results are consistent with the findings from several other translations of the TAS-20 as well as with the original English version (11). Although the 4-factor model showed adequate fit, its PR factor performed poorly; thus removing this model from further consideration. Zhu, Yi, Yao, Ryder, Taylor, and Bagby (12) found that the 4-factor model showed a slightly better fit for their data than the standard 3-factor model in a Chinese student sample, but not in a clinical sample; however, they preferred the more well- established standard 3-factor model based on Müller, Bühner and Ellgring’s (24) assertion that CFAs may be biased in favor of more complex models.

A limitation of this study was the use of a student sample, which could have potentially influenced the resulting factor structure of the TAS-20-Ro. It is possible that the factor structure of the TAS-20-Ro may differ between clinical and nonclinical samples. However, the three factor structure of the English version of the TAS-20 was derived initially with a student sample, and was subsequently replicated in clinical and community samples (8, 19). For the Chinese translation of the TAS- 20, the same three-factor structure was obtained in both student and clinical samples, but a better fit was found in the student sample (12). Nonetheless further research to explore the factor structure of the TAS-20-Ro in a clinical sample is necessary, as replication of the standard three- factor structure would increase generalizability of the scale to the populations that are likely to benefit most from the measure. A second limitation of the current study is the gender imbalance in the Romanian sample, with only 12.8% of the participants being men. This imbalance could potentially affect the factor structure of the TAS-20- Ro, although the three-factor structure has been replicated separately with men and women for the English version of the TAS-20 (19). Future research should explore this more systematically. Further studies are also needed to evaluate the convergent and discriminant validity of the TAS-20- Ro.

Acknowledgements

We would like to give special thanks to some of the people who helped make this project possible: Diana Iacobescu, for her assistance with translation of the TAS-20, Andrei Solomon, for developing the websites used for data collection, and Andrea Szabo for her help with data collection in Romania.

Abbreviations

BBU – Babes Bolyai University

CFA – Confirmatory Factor Analyses

CFI – Comparative Fit Index

DDF – Difficulty Describing Feelings DIF – Difficulty Identifying Feelings EOT – Externally Oriented Thinking IM – Importance of emotions

MIC – Mean Inter-item Correlations

PR – Pragmatic Reasoning

RMSEA – Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation

SD – Standard Deviation

SPSS – Statistical Package for Social Sciences

TAS-20 – the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale

TAS-20-Ro – the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale, Romanian translation

TLI – Tucker-Lewis Index

WRMR – Weighted Root Mean square Residual WLSMV – Weighted Least Squares Means and Variances

REFERENCES

1. Taylor GJ, Bagby RM. The alexithymia personality dimension. In: Widiger TA, (ed). The Oxford handbook of personality disorders. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012, 648-673. 2. Taylor GJ, Bagby RM, Parker JDA. Disorders of affect regulation: Alexithymia in medical and psychiatric illness. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

3. Lumley MA, Neely LC, Burger AJ. The assessment of alexithymia in medical settings: Implications for understanding and treating health problems. J Pers Assessment 2007; 89: 230-246.

4. Nemiah JC, Freyberger H, Sifneos PE. Alexithymia: A view of the psychosomatic process. In: Hill OW, (ed). Modern trends in psychosomatic medicine, vol 3. London, England: Butterworths, 1976, 430-439.

5. Parker JDA, Keefer K, Taylor GJ, Bagby RM. Latent structure of the alexithymia construct: a taxometric investigation. Psychol Assess 2008;20: 385-96.

6. Jórgenson MM, Zachariae R, Skytthe A, Kyvik K. Genetic and environmental factors in alexithymia: A population-based study of 8,785 Danish twin pairs.

Psychother Psychosom 2007; 76: 369-375.

7. Taylor GJ, Bagby RM. Psychoanalysis and empirical research: The example of alexithymia. J Am Psychoanal Assn 2013;61: 99-133.

8. Bagby RM, Parker JDA, Taylor GJ. The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale-I. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. J Psychosom Res 1994;38: 23-32.

9. Bagby RM, Taylor GJ, Parker JDA. The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale-II. Convergent, discriminant, and concurrent validity. J Psychosom Res 1994;38: 33-40.

10. Taylor GJ, Bagby, RM. Alexithymia and the five-factor model of personality. In: Widiger TA, Costa Jr PT, (eds). Personality disorders and the five-factor model of personality, third edition. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2013, 193-207.

11. Taylor GJ, Parker JDA, Bagby RM. The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale IV. Reliability and factor validity in different languages and cultures. J Psychosom Res 2003;55: 277-83.

12. Zhu X, Yi J, Yao S, Ryder AG, Taylor GJ, Bagby RM. Cross-cultural validation of the Chinese translation of the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale. Compr Psychiat 2007;48: 489-496.

13. Tsaousis I, Taylor GJ, Quilty L, Georgiades S, Stavrogiannopolous M, Bagby RM. Validation of the Greek adaptation of the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale. Compr Psychiat 2010;51: 443-48.

14. Taylor GJ, Quilty LC, Bagby RM, Starostina EG, Bogolyubova ON, Smykalo LV, Skochilov RV, Bobrov AE. Reliability and validity of the Russian version of the 20-Item Toronto Alexithymia Scale. Sozialnaya i clinicheskaya psikhiatriya (Social and Clinical Psychiatry) [rus], 2012;22: 20-25.

15. Haita M, Nistor M, Szabo A. Alexitimia la trei estantioane independente: agenti de politie, subofiteri din fortele terrestre si aeriene. Simpozionul national de psihologie al politiei romane – editia a-IV-a. Bucharest: MAI, 2010.

16. Lala A, Bobirnac G, Tipa R, Davila C. Stress levels, alexithymia, Type A and Type C personality patterns in undergraduate students. J Med and Life 2010;3: 200-205.

17. Buchanan T. Online assessment: Desirable or dangerous? Profess Psychol Res Pract 2002;33: 148-154.

18. Bagby RM, Ayearst LE, Morariu RM, Watters C, Taylor GJ. The internet administration version of the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale

(TAS-20-IV). Psychol Assess, under review.

19. Parker JDA, Taylor GJ, Bagby RM. The 20-Item Toronto Alexithymia Scale III. Reliability and factorial validity in a community population. J Psychosom Res 2003;55: 269-275.

20. Del Greco L, Walop W, Eastridge L. Questionnaire development: 3. Translation. Clin Epidemiol 1987;136: 817-18.

21. IBM SPSS Statistics. SPSS 20.0 for Windows user’s guide. Chicago: SPSS, Inc, 2010.

22. Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. Computer software and manual. 6th Ed. Los Angeles: Muthén and Muthén, 2011.

23. Flora DB, LaBrish C, Chalmers RP. Old and new ideas for data screening and assumption testing for exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Front Psychol 2012; 3: 1-21.

24. Müller J, Bühner M, Ellgring H. Is there a reliable factor structure in the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale? A comparison of factor models in clinical and normal adult samples. J Psychosom Res 2003;55: 561-68.

25. Yu CY. Evaluating cutoff criteria of model fit indices for latent variable models withbinary and continuous outcomes. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, 2002.

26. Marsh HW, Hau KT, Wen Z. In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis- testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Structural Equation Modeling 2004;11: 320- 341.

27. MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol Methods 1996;1:130-149.

28. Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric theory, 3rd ed. New York: McGraw Hill, 1994.

29. Simms LJ, Watson D. The construct validation approach to personality scale construction. In: Robins RW, Fraley RC, Krueger RF (eds). Handbook of research methods in personality psychology. New York: Guilford Press, 2007, 240-258.

30. Clark LA, Watson D. Constructing validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. Psychol Assess (Special Issue: Methodological issues in psychological assessment Research) 1995;7: 309-319.

31. Simonsson-Sarnecki M, Lundh L, Torestad B, Bagby RM, Taylor GJ, Parker JDA. A Swedish translation of the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale: Cross validation of the factor structure. Scand J Psychol 2000; 41:25-30.

***

Raluca A Morariu: raluca.a.morariu@gmail.com

Lindsay E Ayearst: layearst@utsc.utoronto.ca