SUICIDE RISK ASSESSMENT IN CLINICAL PRACTICE – A SWEDISH EXPERIENCE

Abstract

Conform statisticilor OMS, la fiecare 40 de secunde undeva in lume o persoana decedeaza ca urmare a unui act suicidar. Consecintele asupra familiei, cercului de apropiati si comunitatii sunt devastatoare si persista in unele cazuri pentru tot restul vietii. Avand in vedere dimensiunile si impactul acestui fenomen, in prezent suicidul este considerat o problema majora de sanatate publica iar preventia lui un obiectiv prioritar pentru sistemele sanitare din intreaga lume. In Suedia, ca si in numeroase alte tari ale lumii exista o preocupare constanta a asociatiilor profesionale si institutiilor guvernamentale pentru imbunatatirea ghidurilor clinice si a protocoalelor de lucru referitoare la ingrijirea pacientului cu risc suicidar. O pondere semnificativa in cadrul programelor regionale de ingrijire o detin protocoalele de lucru pentru evaluarea structurata a riscului de suicid. Articolul propune o trecere in revista a unui astfel de protocol cu discutii asupra aspectelor importante bazandu-se atat pe informatii din literatura de specialitate cat si pe experienta clinica recenta a autorului ca medic specialist in sistemul psihiatric suedez.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines suicide as one’s deliberate act of self-destruction. Often described as an impulsive act, it is predominantly the outcome of a genuine suicidal process involving a gradual progression from the loss of all hope to the actual planning of the suicidal act. As this process may span long periods of time, sometimes years (1), numerous authors consider that many cases of suicide (actually a vast majority) can be prevented (2,3). Properly assessing at which exact stage in the suicidal process the patient is creates optimal conditions for an adequate intervention (4). Suicide risk assessment, as it is currently done in Sweden, is a s t r u c t u r e d a p p r o a c h p e r f o r m e d a c c o r d i n g t o recommendations and clinical guidelines outlined in regional healthcare programs.

STRUCTURED ASSESSMENT OF SUICIDE RISK – WORKING PROTOCOL (1)

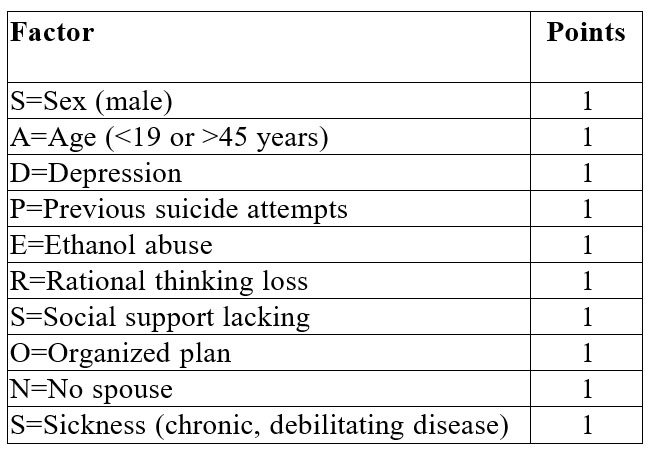

1.ASSESSING RISK FACTORS

There is a long list of factors known to increase the risk of suicide. We consider demographic factors (such as age, sex, marital status), unemployment, the lack of a functional social support network, underlying mental pathology, somatic problems (especially those pathologies involving or expected to involve physical pain in their course), substance abuse or addiction, separation, suicide among family members or close friends and a personal history of attempted suicide. This last factor is deemed to be the most important of known risk factors (5); the more violent the methods previously used, the higher the risk for a new attempt (6).

To have a clear, fast and structured image on existing risk factors, we will use SAD – the Sad Persons Scale (7); the resulting score is documented in the patient’s record. (Table 1)

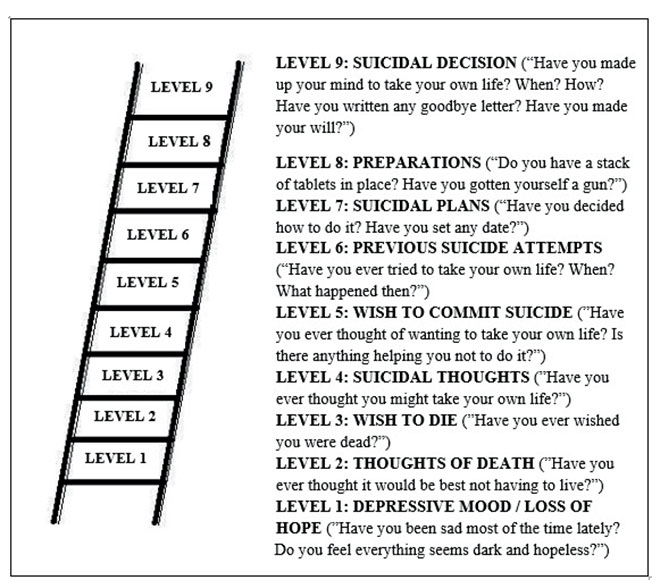

2.SUICIDAL PROCESS MAPPING USING THE “SUICIDE LADDER”

The “Suicide Ladder” (8) is a tool used to

measure how far along the patient has gotten in the suicidal process, from depressive mood and feeling of hopelessness to making active plans and preparations towards committing suicide. Questions are organized in such a way so as to look progressively into this process. The investigator will stop at that specific stage of the process when the patient’s answer is a plausible denial. (Fig.1)

Figure 1. Suicide Ladder (8) – sample questions corresponding to each level

Table 1. SAD PERSONS scale. Source: Patterson et al. (7)

Results of this assessment must be documented in the patient’s record. An example of standard statement is: “Suicide Ladder shows that the patient seems to acknowledge his/her wish to die, but plausibly denies suicidal thoughts or plans”.

3.REVIEW OF RISK SITUATIONS / TRIGGERS AND PROTECTIVE FACTORS

It is a well-known fact that risk stems out of a patient’s experience about a particular circumstance rather than the circumstance itself. Special attention should be paid to the feelings of loneliness, despair and hopelessness, poor impulse control, sleep deprivation, chronic physical pain, anxiety attacks, loss or threatened loss of a key person. Experienced social humiliation (the loss of one’s job, for instance) and professional reinsertion, which may entail painful clashes, carry a higher risk. The use of alcohol or incipient abstinence may be difficult moments when the patient’s ability to manage their suicidal ideation is impaired. Violence (by or against the patient) may be trigger for the suicidal act (9).

A thorough investigation of a patient’s history also reveals protective factors, including the existence of a functional social support network and the patient’s feeling of belonging; personal, cultural or religious values according to which the suicidal act is taboo; dependent children; fear of physical pain or mutilation following a self-aggressive act.

The review of risk situations and protective factors must always be rooted in patient’s reality as their significance is individual. The patient’s feedback is crucial. It is not uncommon for the patient to identify themselves the circumstances increasing the risk of suicide or decreasing suicidal ideation. Results of this review and discussions with the patient on the topic must be documented in the patient’s record.

4.USE OF CLINICAL ASSESSMENT SCALES AND EVALUATION TOOLS

Such structured assessment tools represent an important help for the practitioner; their use is recommended in assessment guidelines and protocols, always with the proviso that they can only aid in and never replace clinical judgment (10).

To assess a patient who has not yet attempted suicide, we have often used the SSI-Scale for Suicide Ideation (11). This scale ensures a multifaceted scoring of the suicidal process: the patient’s attitude towards life or death, the nature of suicidal thoughts (duration, frequency, the sense of being in control of the act in case of suicidal impulses, arguments for and against the suicidal gesture), the nature of the imagined attempt (planning, timing, method, method accessibility, the feeling of being able to actually do it), preparations (goodbye letter, finals actions such as writing one’s will, making donations, signing life insurances, etc).

After an attempted suicide, patients should be assessed using SIS – Suicidal Intent Scale (12), which enables a thorough review of the objective and subjective circumstances around the actual attempt. Issues such as the presence or absence of someone else near the patient, measures taken by the patient to prevent anyone else from getting near them for help, the timing of the attempt, trying to ask for help during or after the attempted suicide, and the type of attempt (planned or impulsive) are considered. Of equal importance is the patient’s own perceptual expectancy of the outcome, for instance if the administered dose of tablets was thought to be fatal or not. Finally, this scale provides an image of the severity of the actual suicide attempt and inherently plays a major part in assessing any subsequent suicide risk.

We always include and document in the patient’s medical record their own rating of the risk of committing suicide. The patient rates this risk with a grade from 1 to 10, where 1 is “I will never take my own life” and 10 ”I have made up my mind, I do not want to live anymore”.

5.INTERVIEWING FAMILY MEMBERS

Family members may only be interviewed with the patient’s prior consent. Possible types of direct verbal (clear-cut messages such as “I kill myself if you leave”) or indirect verbal (“I cannot continue to live like this”) and direct non-verbal (collects pills, procures a gun, etc) or indirect non-verbal (making one’s will, signing an insurance policy, etc) suicidal communications may come up. This discussion helps complete the image on the patient’s overall situation with information about life circumstances, risk factors, triggers for suicidal thoughts and resources that might and must be used for the treatment plan.

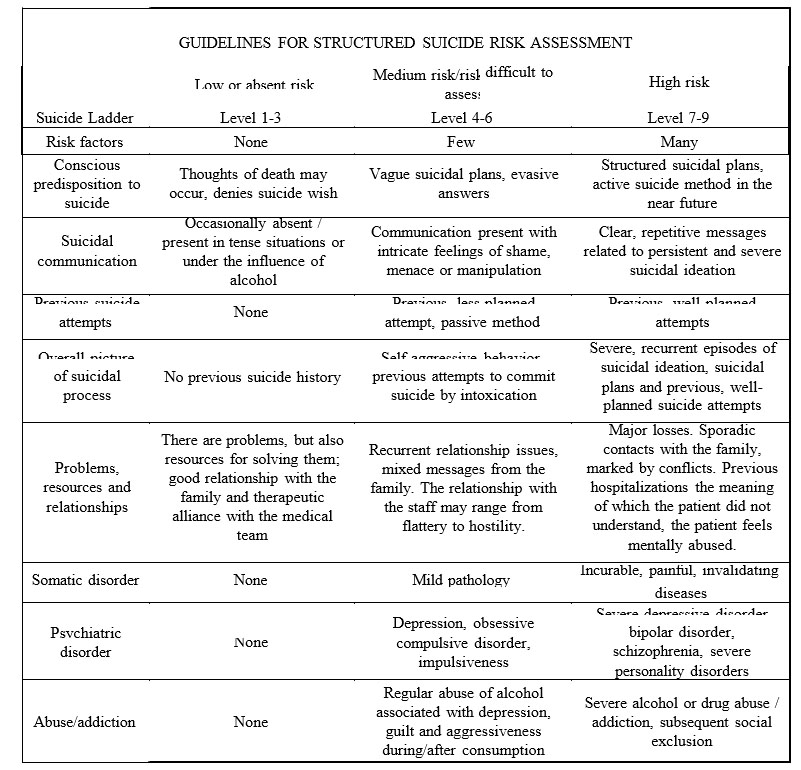

6.GLOBAL ASSESSMENT OF THE ACTUAL SUICIDE RISK

This approach should begin by streamlining the information obtained during the previous stages of the process. Depending on severity, the risk will be rated as low, medium or high. It is not uncommon to see “the suicide risk is difficult to assess” as the most appropriate rating, which means that the assessor cannot exclude a major risk. The lack of proper contact with the patient during the interview, the patient’s attitude of rejecting the dialogue, a patient under substance influence, conflicting information may be as many reasons underlying such difficulty in rating the risk.

A practical way to embed insights collected so far and to help assess the severity of the suicide risk is described in the table below (13). (Table 2)

7.COMPREHENSIVE DOCUMENTATION OF THE SUICIDE RISK ASSESSMENT IN THE PATIENT’S RECORD

All important aspects must be written down in the patient’s medical record. This is how the health practitioner justifies their clinical judgment, the reasons for the risk rating and consequently their choice of the best therapeutic approach. This assessment is also important for other members of the medical team, who have therefore access to vital information in order to ensure a proper attitude in their relationship with the patient. Improved know-how of the therapeutic team translates into high-quality care in the medical practice. As a matter of fact, in the Swedish healthcare system, the suicide risk assessment is not exclusively the duty of the attending physician; the psychologist or the nurse in charge regularly assesses and documents the suicide risk in the patient’s record and turns to the physician for help whenever necessary.

Table 2. Suicide risk assessment criteria -risk categories. Source: (13)

Example of documenting the suicide risk assessment in the patient’s electronic file (fictitious patient):

“Patient with multiple risk factors: male, 50, prior diagnostic of recurrent depressive disorder, under treatment for 10 years; multiple therapeutic attempts involving various antidepressants, no significant improvements (as the patient describes it). Patient feels like he has a poor quality of life due to multiple relapses and is reluctant to new therapeutic trials for fear of side effects. Currently unemployed, he was laid off 4 months ago for not properly fulfilling his job responsibilities. Lots of guilt and shame because of this. Financial distress. He lives alone; wife died 3 years ago, no children. No relatives living within call, has a sister who lives in another town and whom he sees twice a year. Poor social support network, there is only one neighbour that the patient sees about twice a week. Patient has avoided meeting him lately because he sees “no point in doing it anymore”. Describes feelings of hopelessness; the future seems dark. His mother committed suicide when he was

10; the patient recalls that she “used to be sad all the time…just like me”. He experiences chronic back pain for which the family doctor prescribed a treatment. Over the past few months, the patient requested twice that the current dose of medication be increased as it was no longer effective, but his request was denied. He felt humiliated and “treated like a drug addict”. He denies alcohol use. Medical history shows no previous suicide attempts.

According to the Suicide Ladder, the patient displays suicidal ideation in the form of thoughts recurring several times a day, especially when he is in pain and in the evening when preparing to go to sleep. He has succeeded in resisting these thoughts so far, but feels this is more and more difficult and he is tired. Despite denying suicidal plans, he admits that he started to collect pills one month ago, though he later changed his mind and gave them back to the drug store in order to “no longer keep them in the house”.

Medical history does not show any protective factor. The patient himself says that “I have no reason that might stop me from dying today”.

Rating scales: Patient’s self-rating of the risk of taking his own life today is 6 on a scale of 1 to 10. He says:”it may go up to 9 when I am in pain”. SSI: 22 points The patient has no family to see him off for admission to the hospital. He does not want us to contact his sister because “we see each other very rarely and our relationship is not so close anyway”.

The suicide risk is rated as high both now and in the long term due to the presence of major depressive disorder, multiple risk factors (SAD: 6 points) and the lack of protective factors, to a difficult psychological and social situation that the patient sees as stigmatizing and to the lack of proper social support network, in conjunction with the outcome of clinical scale scoring. A particular issue is the chronic pain identified by the patient as a major trigger of suicidal ideation, which significantly increases the patient’s likelihood of committing suicide.”

The structured suicide risk assessment must be repeated and documented at specific key time points (changes in patient’s clinical condition, before modifying the supervision level, before granting of home leaves, before discharge), but also whenever necessary (5). Last but not least, we should remember that a properly conducted assessment interview may and must be a crisis intervention enabling an empathic contact with the patient and providing them with a secure environment where they can talk about their thoughts.

References:

1.Lindström K, Elofsson B, Ferm M et al. Vårdprogram om suicidprevention för vuxna.Jönköping: Landstinget i Jönköping län, 2005, 1-28.

2. Wasserman D (red). Suicide: An Unnecessary Death. London: CRC Press, 2001, XXI-29.

3. World Health Organization. Preventing Suicide: a global imperative. Geneva: WHO Press, 2014, 1-92.

4.Runeson B, Samuelsson M, Åsberg M. Vård av självmordsnära patienter-en kunskapsöversikt. Socialstyrelsen, 2003,1-83.

5.Renberg E, Sunnqvist C, Westrin Å, Waern M, Jokinen J, Runeson B. Suicidnära patienter-kliniska riktlinjer för utredning och vård. Stockholm: Svenska Psykiatriska Föreningen, 2013, 1-92

6. Runeson B, Tidemalm D, Dahlin M, Lichtenstein P, Långström N. Method of attempted suicide as predictor of subsequent successful suicide: national long term cohort study. BMJ 2010;341:c3222.

7. Patterson WM, Dohn HH, Bird J, Patterson GA Evaluation of suicidal patients: the SAD PERSONS scale. Psychosomatics 1983; 24(4):343-5, 348-9.

8. Beskow J. (red). Självmord och självsmordsprevention. Om livsavgörande ögonblick.Lund: Studentlitteratur, 2000

9. Capusan A, Andersson B. Vårdprogram för suicidprevention hos vuxna. Östergötland: Landstinget i Östergötland, 2010, 1-26.

10. Runeson B. Regionalt Vårdprogram-Suicidnära patienter. Stockholm: Stockholms läns landsting, 2010, 1-78.

11. Beck A.T, Kovacs M, Weissman, A.. Assessment of suicidal intention: the scale for suicide ideation.J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1979; 47:343–352.

12. Beck AT, Schuyler D, Herman I. Development of Suicidal Intent Scale. In: Beck AT, Resnick HLP, Lettieri J (eds). The prediction of suicide. Bowie, MD: Charles Press,1974, 45-56.

13.Nordlund S, Hellström J, Sparring S. Vårdprogram för suicidnära patienter. Sörmland: Landstinget Sörmland, 2014, 79.

***